This piece is for the people who say, Oh, yes, Ursula K. Le Guin – I really don’t read sci fi. Or, Ursula K. Le Guin, I just love her sci fi novels. Who in either case may not know that this was as fine and thoughtful a poet as any in our time, and essayist; literary critic and public intellectual; and gifted translator. If you’re a poet, a novelist, an essayist; if you’re a reader, and you do not know this side of Le Guin — what a wealth awaits you. Links at the end for the books mentioned are of course not to Amazon, but to IndieBound or Abe Books. For in print books, check with your local independent bookstore.

When we met, I had only two of her books on my shelf, specifically on the feminist book shelf: Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (1989), that was browning around the edges, and the more recent The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (2004). I knew her name, of course, but I had to pull the books out to remember my own connection to essays I had savored—

“Is Gender Necessary? Redux”

“Reciprocity of Prose and Poetry”

“A Left-Handed Commencement Address” (reminding me she had written a novel called The Left Hand of Darkness and now saddening me I never thought to ask, or notice, if we shared left-handedness? or perhaps, absurdly, was that what she saw in me?)

“Being Taken for Granite”

“My Libraries”

“Off the Page: Loud Cows: A Talk and a Poem about Reading Aloud”

“The Writer On, and At, Her Work”

— To remember the vitality, the little jolt of pleasure and heightened awareness at this original, familiar, intimate voice. These were talks at college commencements, library openings, reviews, occasional pieces.

“Introducing Myself” is a performance piece that begins

I am a man. Now you may think I’ve made some kind of silly mistake about gender, or maybe that I’m trying to fool you, because my first name ends in a, and I own three bras, and I’ve been pregnant five times, and other things like that that you might have noticed, little details. But details don’t matter. If we have anything to learn from politicians, it’s that details don’t matter. I am a man, and I want you to believe and accept this fact, just as I did for many years.

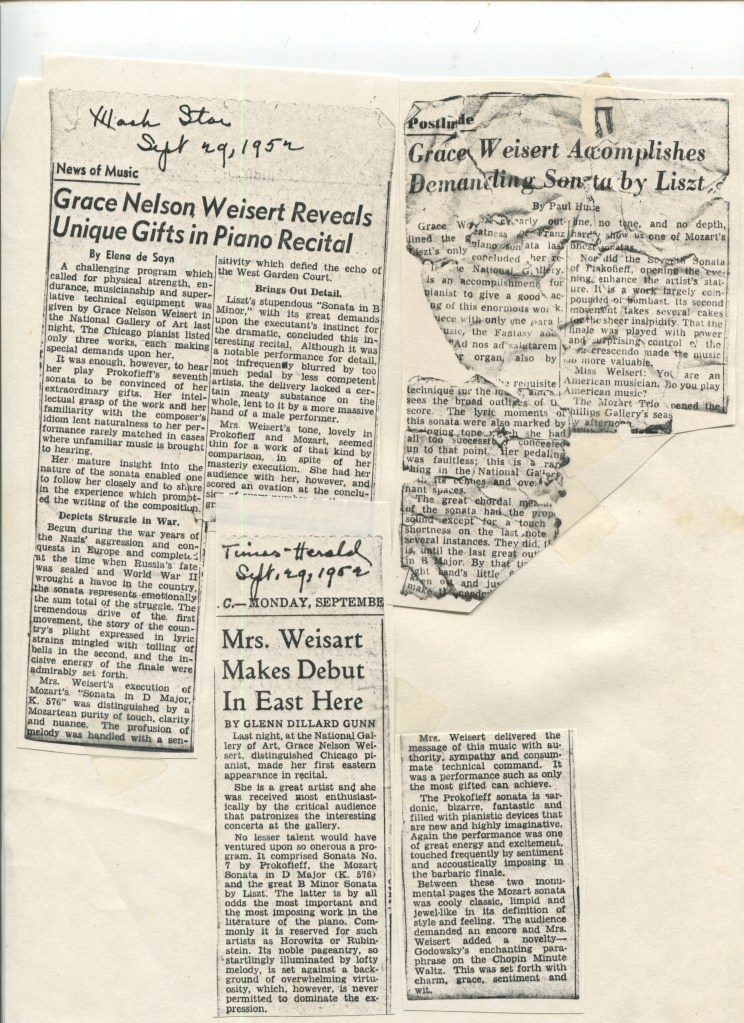

As I read that now, the first essay in The Wave in the Mind, I remember sitting up a little straighter back in 2005 or 2006 as I thought about my mother and the pride she took in thinking like a man, playing the piano like a man, scoring on an IQ test better than any man in our family, joining the men after dinner to talk about real things. That toxic pride that Ursula names and – I’m reaching for a verb, there might have to be a new one – Ursula-izes – in five pages, ending with

Sometimes I think I might just as well exercise my option, stop short in front of the five-barred gate, and let the nazi fall off onto his head. If I’m no good at pretending to be a man and no good at being young, I might just as we ll start pretending that I am an old woman. I am not sure that anybody has invented old women yet; but it might be worth trying.

Ah, but what inventions were yet to come!

Lest you think the essays are all of feminist interest only, there are as many bracing, revelatory pieces about writing and poetry, about the imagination and about our society.

Damn, I am only just now reading “’Forsaking Kingdoms’: Five Poets” (1984) to find

May Sarton is a mere septuagenarian, but count her title list with awe. This is a writer, this is what writers do: fourteen volumes of poetry, seventeen of fiction, two books for kids, and seven books of essays. (Ah, Ursula recognizing kin. I wonder if Sarton was anywhere near Le Guin in the other realm, the one I entered, correspondence and poems and thoughts exchanged with writers whose names I am only beginning to learn about as we each step out of our cherished private, closely held, miraculous friendships to write a short post, an essay, a tribute.)

Continuing on Sarton:

The newest of the lot, Letters from Maine, is mostly easy-going…one may be soothed by the conventionality…but look out. Sudden authority rings like sword steel.

I began re-reading Letters from Maine last spring with a plan to write a “Throwback Thursday” review at the request of Glass: A Journal of Poetry. Always meant to ask Ursula what she thought of Sarton. And Levertov – for some reason I was a little wary of asking her about Levertov, afraid she might not find as much to like as I had. But I needn’t have hesitated — here is what I find in that 1984 essay:

Denise Levertov’s mastery—more than mastery, because she is one of the originators—of contemporary poetic form, informed by a fierce, generous intelligence, can be frightening. This is the charged, overloaded poetry of the age, demanding more of the reader than most of us are willing to give, so we don’t read poetry, we read a thriller or something, and oh, what dolts we are, what wasters of our own brief time—to miss this tenderness, this kind companion in hard times, not trying to sell us anything or scare us or fool us, but going along with us.

And besides, if we did disagree – she disliked the poetry of some of the usual gods we lesser mortals genuflected for, like Seamus Heaney, and even Emily Dickinson! – that would have been fine, too. Actually, she would have been curious about what I found to like, and I would have wished I had more to offer than received wisdom and the line about digging with a pen.

The Wave in the Mind takes its title from a letter by Virginia Woolf (writing to Vita Sackville-West, 16 March 1926) that Le Guin quotes at the beginning of the book and that I would like to commit to memory:

As for the mot juste, you are quite wrong. Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can’t use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can’t dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it. But no doubt I shall think very differently next year.

— Virginia Woolf, writing to Vita Sackville-West, 16 March 1926

Another topic I wish I’d raised with her. When I was planning a workshop on walking and poetry, where indeed part of the point is the rhythm that walking provides, we did discuss the effect of/interaction of walking and poetry, but not that wave in the mind, which I am feeling a bit right now. Rhythm, with a little vertigo.

From 2010 to September 25, 2017, Ursula wrote a blog on topics ranging from the political to the literary, the universal to the personal (the personal often in the person of the cat Pard and his annals (with wonderful pictures). Many of these pieces have been collected in a volume published in December, 2017 and titled for her second post, in 2010, No Time to Spare:Thinking About What Matters (collected and introduced by the celebrated fiction writer Karen Joy Fowler). The title piece was occasioned by a question on the Harvard 60th anniversary survey, “What do you do with your spare time?” You can imagine what Ursula thought of that. (In the introduction to “The Hope of Rabbits: A Journal of a Writer’s Week” she writes “I attended a women’s college that was embedded like a seed pearl in a gigantic male oyster.”)

Online, the blog is in separate pages by year, from http://www.ursulakleguin.com/Blog2010.html (the beginning) to http://www.ursulakleguin.com/Blog2017.html#New (the last). Pieces included in the book are deleted, a link to the book added, but there is still much here to savor that apparently did not get included, including much about Pard (with the lovely pictures).

2019 note: The blog is still accessible but at an archive site– http://ursulakleguinarchive.com/Blog-Index.html

Oh wait – I should have known that in the many and multifarious ways of UKL (or her digital accomplices), the posts with the “annals of Pard” tag would be collected in one place, here http://bookviewcafe.com/blog/tag/annals-of-pard/ . Full of delight and uncanny insight into the mind of a cat, these are in the same league as Don Marquis or E.B. White.

Many of these pieces are laugh-out-loud funny – for example, “#44. People I don’t want to hear any more about.”

But the blog pieces are also the reflections of one of our great public intellectuals wrestling with the major events of our time – the place of religion in our lives (“An Attempt to Think as a Free Thinker”), the occupation of the Malheur Refuge headquarters (“#110. Thirty-Five Days”), a piece about the 2016 election (“119. The Election, Lao Tzu, a Cup of Water” that concludes with this:

I know what I want. I want to live with courage, with compassion, in patience, in peace.

The way of the warrior fully admits only the first of these, and wholly denies the last.

The way of the water admits them all.

The flow of a river is a model for me of courage that can keep me going — carry me through the bad places, the bad times. A courage that is compliant by choice and uses force only when compelled, always seeking the best way, the easiest way, but if not finding any easy way still, always, going on.

The cup of water that gives itself to thirst is a model for me of the compassion that gives itself freely. Water is generous, tolerant, does not hold itself apart, lets itself be used by any need. Water goes, as Lao Tzu says, to the lowest places, vile places, accepts contamination, accepts foulness, and yet comes through again always as itself, pure, cleansed, and cleansing.

Running water and the sea are models for me of patience: their easy, steady obedience to necessity, to the pull of the moon in the sea-tides and the pull of the earth always downward; the immense power of that obedience.

I have no model for peace, only glimpses of it, metaphors for it, similes to what I cannot fully grasp and hold. Among them: a bowl of clear water. A boat drifting on a slow river. A lake among hills. The vast depths of the sea. A drop of water at the tip of a leaf. The sound of rain. The sound of a fountain. The bright dance of the water-spray from a garden hose, the scent of wet earth.

This is followed by a poem, “Meditation”. I am sure I am not alone in finding great comfort in this piece, and in Lao Tzu, in such times as ours.

“Matter” is a word that matters to Le Guin, I notice as I look at the two most recent essay collections, No Time To Spare and Words Are My Matter: Writings about Life and Books 2000-2016”.

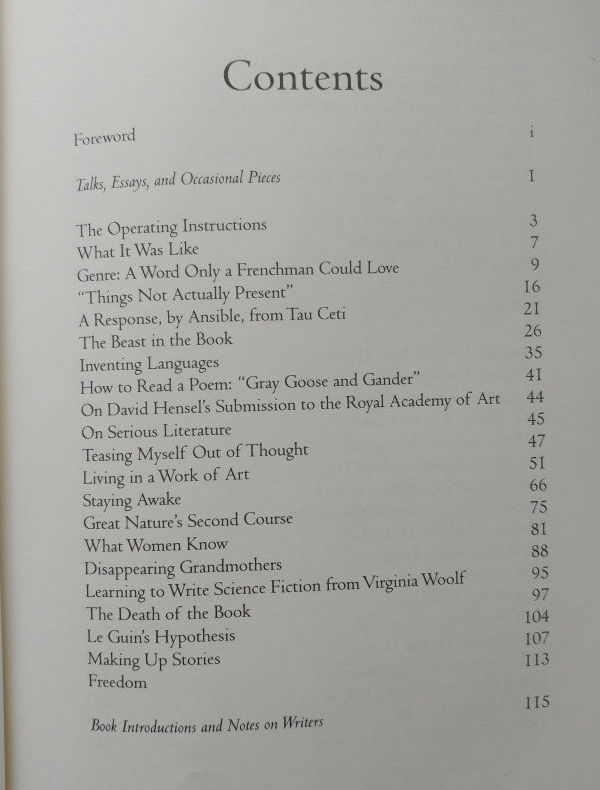

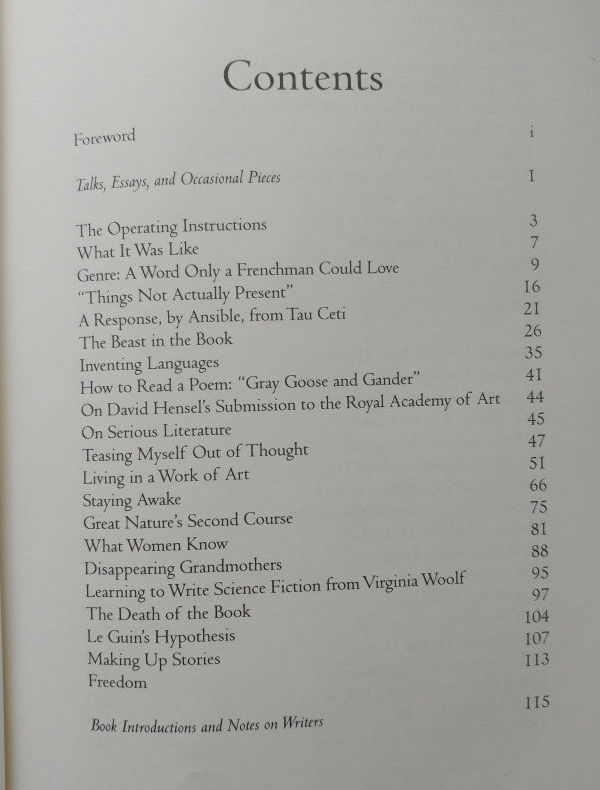

The latter I was not aware of until I saw it in a display on the front counter at Flyleaf, my local Chapel Hill independent bookstore, shortly after Ursula died. Although she would often email me a poem she was working on (amazingly, to ask my opinion!), she almost never announced her new publications. So I assumed the book was a combination of some earlier essays from The Wave in the Mind plus some written since. It turns out there is one repeat (“The Operating Instructions”), but mostly these are all previously uncollected, just that mere fraction of what Ursula Le Guin was doing over the last decade and a half. The table of contents shows the range, and if it does not tempt you to go to your local bookstore and get the book, then – well, I don’t know. Here’s the list for the first section:

The book reviews include pieces on Margaret Atwood, Geraldine Brooks, Italo Calvino, Margaret Drabble, Barbara Kingsolver, Doris Lessing, and Donna Leon (Donna Leon! oh my, oh damn, how did I not know she read my favorite mystery writer?). And at the end, a gift, for anyone who has gone to a writer’s retreat, “The Hope of Rabbits: A Journal of a Writer’s Week,” about her time at Hedgebrook. In the introduction to that diary there’s what I believe will be all that needs to be said — and without ranting — about the virtues of handwriting, in part:

“I think about the humane pace of longhand, and how one is constantly looking away from the notebook at things around it, near or far, changing position as one sits, doodling in the margin while working out a transition, half-consciously noticing the slant of the sunlight, the advance of shadows, the color of the sky; fully absorbed in the work, and yet open to the surrounding world…”

A silver lining of my not keeping up well with the recent writings is that I still have so much to read that’s new. Though, as I dip back into the books that are dog-eared, I realize as well that almost any of these pieces are as fresh and readable today as they were the first time.

What reading the essays, reviews, and talks allows, that I don’t believe the fiction does, is hearing the human voice of the person Ursula Kroeber Le Guin. To read these works is to feel one is in her presence. Nothing on earth like it.

***

Ursula Le Guin also had a significant career as a translator, notably of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching, but also in The Twins, the Dream/Las Gemalas, El Sueno, a volume of mutual translation with the Argentine poet Diana Bellessi (each translates the other), and in 2003, The Selected Poems of Gabriela Mistral, which I’ll attempt to do justice to in another blog piece.

Books discussed: Essays, talks, reviews

The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (from IndieBound, new)

Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (from AbeBooks, used)

No Time to Spare:Thinking About What Matters (from IndieBound, new)

Words Are My Matter: Writings about Life and Books 2000-2016 (from IndieBound, new)

I’ve noticed how often poets I know will post something about food on their social media sites — delicious food, often with pictures. In the summer, there are usually tomatoes and other fruits of the garden; in the winter, it’s often stews and soups.

I’ve noticed how often poets I know will post something about food on their social media sites — delicious food, often with pictures. In the summer, there are usually tomatoes and other fruits of the garden; in the winter, it’s often stews and soups.