Today: The National Endowment for the Humanities in tatters. The Kennedy Center taken over by a Philistine (that may be an insult to Philistines). Libraries closed and books banned. Words expurgated from government websites.

On and on with echoes of Nazis branding real art “degenerate,” Soviet Russia requiring only “Socialist Realism” art, and here, reminders of the effects of the McCarthy era on film and literature. We all know how Hollywood writers and actors were blacklisted, and we’re not surprised to learn of the “complying in advance” of government employees and others in that era who kept their heads down and, like my father when he worked for the State Department, insisted their family not talk politics even with friends.

And when we cancel Washington Post subscriptions because of owner Jeff Bezos’ declared censoring of editorial freedom, we lament the loss of the courageous speaking-truth-to-power Post of Katherine Graham, Woodward and Bernstein, Herblock.

So you may be surprised to know that the chill of the Red Scare did affect the Washington Post at the height of the McCarthy era in, of all things, their music criticism.

Older music lovers may know the name of the longtime Post music critic, Paul Hume. Others may remember his name as a historical footnote—the critic whose 1950 blistering review of Margaret Truman’s singing inspired her father Harry to threaten Hume with a punch in the nose, or elsewhere. But for me, Hume is the critic who wrote a review of the first recital my mother, Grace Nelson Weisert, played in the National Gallery. A good review, but with an entirely extraneous conclusion that I’ll explain after some background.

One of the inducements my father had offered my mother for moving, in 1952, from Chicago to Washington (so that he could take a government job) was that she could resume studying with her longtime piano teacher, Glenn Dillard Gunn, and resume her public career after a long hiatus. Gunn, who had studied with Busoni and who had taken my mother on as a student for free when she was 12, had made his own Chicago to Washington move a few years earlier and was both a teacher and music critic for the Washington Times-Herald.

So we moved, and my mother went twice a week to Gunn’s studio on R Street, often with the seven-year-old me, and worked up a program she would perform at the National Gallery. The National Gallery music series in one or the other of the two Garden Courts was highly respected and sure to be attended by the reviewers of all three Washington papers, The Post, The Evening Star, and the Times-Herald.

Gunn wanted her to try something new, to American ears, and fully exercising her considerable gifts, so the program would begin with the most stirring of Prokofiev’s War Sonatas, the Seventh. Dissonant, modern, powerful. No one else was playing it in those days, in that town.

It was quite a program, I realize now, Gunn clearly wanting his star student to make a splash in her Washington debut. After the Prokofiev and the Mozart Sonata in D Major, the program would end with the massive Lizst B Minor Sonata. But her mastery of that challenge (see the reviews below) wasn’t what Hume would leave his readers with.

No, after acknowledging my mother’s skill and talent, though with reservations, Hume left them with something else, and I think it says all you need to know about how, in another era in this country, a powerful out-of-control official—thankfully then, only a senator not a president—could affect even a musical review, twisting even an esteemed music critic into a pretzel of ostentatious and entirely gratuitous patriotism.

It is—ironic isn’t the word, I don’t know what is—odd?—that today what is suspect is far from anything Russian, but the cowardly kowtowing, the compliant and shameful surrender is little different from what we see today from certain powerful law firms, colleges, and other cowardly institutions.

This is how the review — a music review — ended:

“Miss Weisert, you are an American musician. Do you play American music?”

————————————————————————————–

From Wikipedia: Of the War Sonatas, biographer Daniel Jaffé has argued that Prokofiev, “having forced himself to compose a cheerful evocation of the nirvana Stalin wanted everyone to believe he had created” (i.e. in Zdravitsa) then subsequently, in these three sonatas, “expressed his true feelings”.

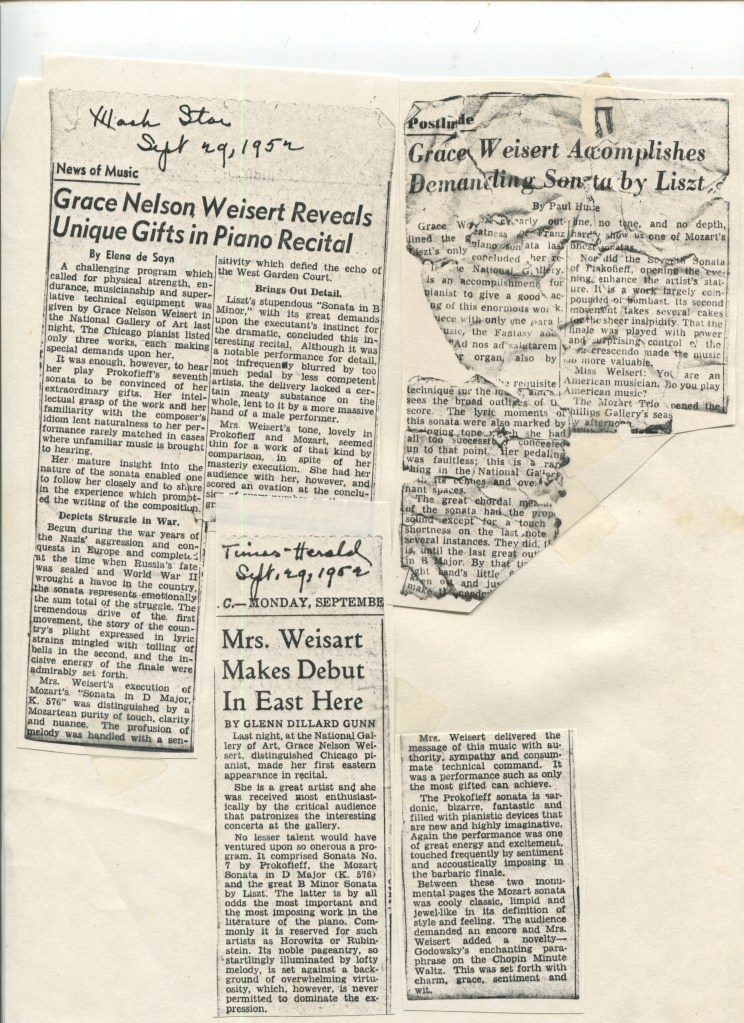

Program and reviews below. Sadly, the Washington Post review (“Grace Weisert Accomplishes Demanding Sonata By Liszt”) had apparently disintegrated before my brother made this copy years ago, but if you look closely you can see his question, the last paragraph before he goes on to write about another concert (the Mozart Trio).

I should add that Hume was in a very different frame of mind six years later when my mother performed at the National Gallery again. Gone was his sour tone and just about everything in that review was positive.

Did he remember the earlier dismissal? Regret it? We’ll never know, but at least here his focus was entirely on the music and the performance.

June 16, 1958, from the Washington Post: